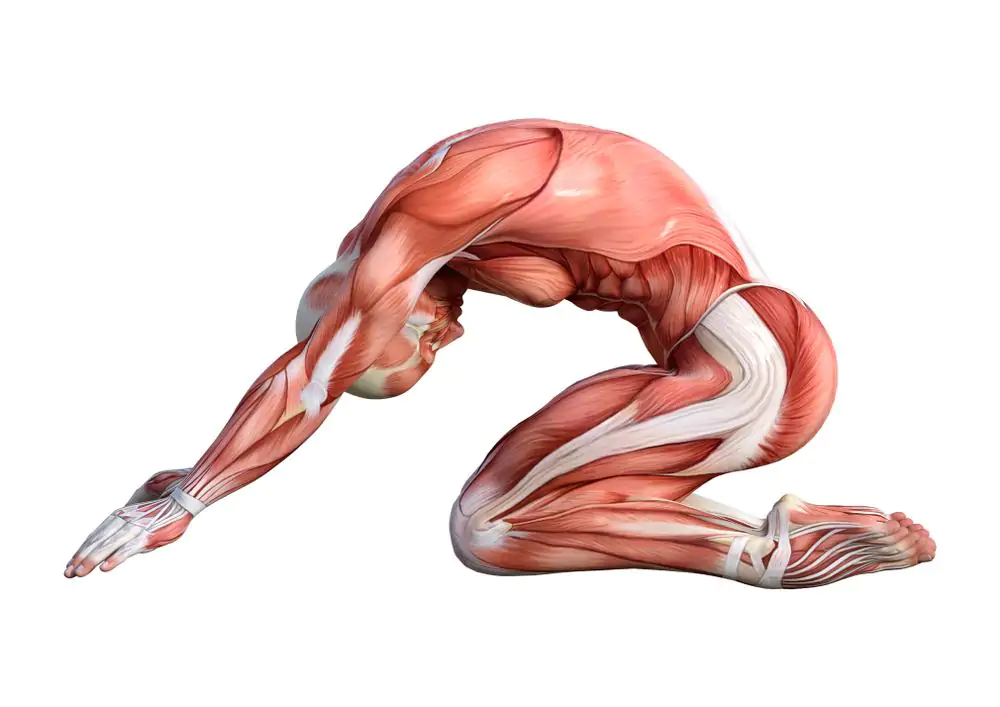

Understanding yoga anatomy transforms your practice from simply copying poses to intelligently moving your body with awareness and purpose. This yoga anatomy guide breaks down the complex relationship between your skeletal system, muscles, and connective tissues to help you practice safely and effectively.

Whether you’re a beginner learning your first Warrior Pose or an experienced practitioner exploring advanced inversions, knowing how your body works empowers you to move with confidence and avoid common injuries. The human body contains 206 bones, over 600 muscles, and countless joints that work together to create the beautiful movements we call yoga.

This comprehensive guide will help you understand the anatomical principles behind your favorite poses, recognize which muscles are working (and which should be relaxing), and develop a deeper mind-body connection that makes every practice more meaningful.

Understanding the Musculoskeletal System in Yoga

The Foundation: Bones and Joints

Your skeletal system serves five essential functions: providing structure and support, protecting vital organs, facilitating movement, storing minerals, and producing blood cells. In yoga, we primarily focus on how bones create levers for movement and how joints determine our range of motion.

Key joint types in yoga:

- Ball-and-socket joints (hips and shoulders) – Allow the greatest range of motion in all directions

- Hinge joints (knees and elbows) – Permit flexion and extension in one plane

- Pivot joints (neck) – Enable rotation around an axis

- Gliding joints (wrists and ankles) – Allow sliding movements between bones

The most mobile joints in your body are your shoulders, which is why poses requiring shoulder flexibility can feel challenging. Understanding that your hip joint is structured differently than your neighbor’s explains why some people naturally sink into Virasana while others need modifications.

Muscles: The Movers and Stabilizers

Muscles generate force through contraction only—they pull but never push. This fundamental principle explains why we always work with opposing muscle groups, called agonists and antagonists.

Three types of muscle contractions in yoga:

- Concentric contraction – Muscle shortens while working (lifting your leg in standing splits)

- Isometric contraction – Muscle works without changing length (holding plank pose)

- Eccentric contraction – Muscle lengthens while working (lowering from a jump-back)

When you fold forward, your hamstrings (antagonists) lengthen while your hip flexors (agonists) contract to create the movement. Understanding this agonist-antagonist relationship helps you engage the right muscles and release unnecessary tension.

The Spine: Your Yoga Backbone

Spinal Structure and Movement

Your spine consists of 24 vertebrae divided into three regions: 7 cervical (neck), 12 thoracic (mid-back), and 5 lumbar (lower back) vertebrae, plus the fused sacrum and coccyx. Each region has different mobility capacities that directly impact your yoga practice.

Spinal Movement Ranges:

| Movement Type | Cervical | Thoracic | Lumbar | Total Range |

| Flexion (forward bending) | 40° | 45° | 60° | 145° |

| Extension (backbending) | 75° | 25° | 35° | 135° |

| Rotation (twisting) | 50° | 35° | 5° | 90° |

| Lateral flexion (side bending) | 35° | 20° | 20° | 75° |

Notice that your lumbar spine has very limited rotation capacity—only 5 degrees! This explains why yoga twists should primarily come from your thoracic spine, not your lower back. Forcing rotation in the lumbar region can lead to disc problems and chronic pain.

Protecting Your Spine in Practice

The intervertebral discs between each vertebra contain a gel-like nucleus surrounded by fibrous rings. These discs have no direct blood supply, which means they rely on movement to receive nutrients and stay healthy. This is one reason why regular yoga practice benefits spinal health.

However, 80% of people experience debilitating back pain at some point in their lives. To protect your spine:

- Maintain natural curves rather than forcing a flat back

- Distribute movement evenly across all spinal segments

- Engage core muscles to support vulnerable areas

- Avoid extreme flexion combined with rotation

- Move slowly and mindfully, especially in vulnerable positions

Hip Anatomy: The Foundation of Lower Body Movement

Hip Joint Structure

The hip is a remarkably stable ball-and-socket joint where the head of your femur (thigh bone) fits into the acetabulum of your pelvis. Three bones fuse to create your pelvic bowl: the ilium, pubis, and ischium. Your “sit bones” (ischial tuberosities) and “hip points” (anterior superior iliac spine) are important landmarks for alignment.

Six hip movements:

- Flexion – Bringing thigh toward chest (forward folds)

- Extension – Taking leg behind you (Warrior Pose back leg)

- Abduction – Moving leg away from midline (side leg lifts)

- Adduction – Bringing leg toward midline (squeezing block between thighs)

- External rotation – Turning thigh outward (lotus position)

Internal rotation – Turning thigh inward (pigeon pose front leg)

Key Hip Muscles for Yogis

Hip flexors (iliopsoas group):

- Create forward bends and leg lifts

- Often tight from prolonged sitting

- Need strengthening for balance poses and core work

Hip extensors (gluteus maximus and hamstrings):

- Power backbends and standing poses

- Work against tight hip flexors

- Essential for standing balance and transitions

Deep hip rotators (piriformis, gemellus, obturator):

- Control rotation and stability

- Can compress sciatic nerve when tight

- Targeted in “hip opening” sequences

Over 30 muscles cross the hip joint, which is why simply saying you need “hip openers” isn’t specific enough. Tight hip flexors require different stretches than tight external rotators.

Shoulder Complex: Understanding Upper Body Mobility

Three Joints Working Together

Your shoulder is actually three joints working in coordination: the glenohumeral (arm bone to shoulder blade), acromioclavicular (collarbone to shoulder blade), and sternoclavicular (collarbone to breastbone). This complex arrangement creates the body’s most mobile joint.

Unlike the deep hip socket, your shoulder socket is shallow—often compared to a golf ball on a tee. Four rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis) work constantly to keep the arm bone centered in this shallow socket.

Common shoulder movements in yoga:

- Flexion – Arms overhead (upward facing dog, handstand)

- Extension – Arms behind you (reverse prayer, cow face arms)

- Abduction – Arms to the sides (side plank, inversions)

- External rotation – Palms facing up (upward facing dog)

Internal rotation – Palms facing down (chaturanga)

Protecting Your Shoulders

The supraspinatus is the most commonly injured rotator cuff muscle because it travels through a narrow space where it can be compressed. To protect your shoulders:

- Keep shoulder blades stable on your back

- Avoid “winging” shoulder blades in plank positions

- Maintain space between ears and shoulders

- Build strength gradually before attempting advanced arm balances

- Respect individual bone structure variations

Modern desk posture creates rounded shoulders and tight chest muscles. Yoga helps counteract this by strengthening upper back muscles and opening the chest, but progression should be gradual.

The Breath: Anatomical Keys to Pranayama

Diaphragm and Breathing Mechanics

Your primary breathing muscle is the diaphragm—a dome-shaped sheet separating your chest cavity from your abdominal cavity. When it contracts, it flattens downward, creating a vacuum that draws air into your lungs.

Three-part yogic breath anatomy:

- Lower breathing – Diaphragm descends, belly expands

- Middle breathing – Ribs expand laterally and upward

- Upper breathing – Collarbones lift slightly

The chest cavity is compressible like an accordion, while the abdominal cavity is liquid-filled and can only change shape, not volume. This is why deep breathing requires either belly expansion or rib expansion—you can’t compress your organs.

Accessory breathing muscles:

- Intercostals (between ribs) for rib expansion

- Sternocleidomastoid for emergency breathing

- Abdominals for forceful exhalation

- Pelvic floor for breath control and bandhas

Knee and Ankle Anatomy: Protecting Your Lower Joints

The Knee Joint

Your knee is actually two joints: the tibiofemoral (thigh to shin) and patellofemoral (kneecap to thigh). Strong ligaments provide stability: the MCL and LCL on the sides, and the crucial ACL and PCL inside the joint.

Critical alignment principle: Your knee is a hinge joint designed primarily for flexion and extension. Forcing rotation while the foot is planted can tear the meniscus (shock-absorbing cartilage) or damage ligaments.

Safe knee alignment:

- Track kneecap over second/third toe

- Avoid excessive inward collapse (valgus)

- Don’t force rotation in poses like lotus or hero

- Respect pain signals immediately

- Build surrounding muscle strength for joint protection

Ankle and Foot Architecture

arches (medial longitudinal, lateral longitudinal, and transverse) work like springs to absorb impact and propel movement.

Key ankle movements:

- Dorsiflexion – Flexing foot toward shin (squatting, forward folds)

- Plantarflexion – Pointing foot (most backbends, standing on toes)

- Inversion – Rolling foot inward (can strain lateral ankle)

- Eversion – Rolling foot outward (less common, more stable)

Strong, mobile feet and ankles provide the foundation for all standing poses. Many people unconsciously invert their feet (collapse arches inward), which destabilizes the entire kinetic chain up through the knees, hips, and spine.

Planes of Motion: How Your Body Moves in Space

Understanding the Three Cardinal Planes

Every yoga pose moves your body through one or more planes of motion:

Sagittal plane (forward/backward):

- Forward folds and backbends

- Sun salutation movements

- Examples: forward fold, upward dog, cobra

Frontal plane (side-to-side):

- Side bends and lateral movements

- Examples: triangle pose, side angle, gate pose

Transverse plane (rotation):

- All twisting movements

- Examples: revolved triangle, yoga twists, seated spinal twist

Most traditional yoga sequences heavily emphasize the sagittal plane. Adding poses in the frontal and transverse planes creates more balanced strength, flexibility, and coordination.

Flexibility Science: Stretching That Works

Types of Flexibility

Static-passive flexibility – Using gravity or props to hold stretched positions (most common in yoga)

Static-active flexibility – Using muscle strength alone to hold positions (leg lifts, standing splits)

Dynamic flexibility – Moving through range of motion (sun salutations, flowing sequences)

Active flexibility is harder to develop than passive flexibility because it requires both the flexibility to achieve a position and the strength to maintain it without support.

Effective Stretching Techniques

Reciprocal inhibition principle: When you contract a muscle (agonist), its opposite muscle (antagonist) receives a signal to relax. In forward folds, actively engaging your quadriceps helps your hamstrings release and lengthen.

PNF stretching (Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation):

- Move into a stretch position

- Gently contract the muscle being stretched (5-8 breaths)

- Release and move deeper into the stretch

- Rest 48 hours before repeating on the same muscle group

Factors affecting flexibility:

- Joint structure (some joints naturally have more mobility)

- Muscle tissue elasticity (scar tissue reduces flexibility)

- Temperature (warm muscles stretch more safely)

- Time of day (most flexible between 2:30-4:00 PM)

- Hydration (water contributes to tissue mobility)

- Genetics, age, and gender

Practical Application: Anatomy in Common Poses

Warrior Pose Anatomy

Warrior II breakdown:

- Front hip: External rotation, flexion, and abduction

- Back hip: Internal rotation with extension

- Quadriceps working in front leg to stabilize knee

- Gluteus medius preventing hip collapse

- Obliques engaging to maintain upright torso

- Shoulder abductors holding arms horizontal

Forward Fold Mechanics

Standing forward fold requirements:

- Hip flexion (primary movement)

- Hamstring lengthening (antagonist stretch)

- Back muscles lengthening (spine flexion)

- Ankle dorsiflexion (shifting weight forward)

- Quadriceps engagement (reciprocal inhibition helps hamstrings release)

Safe Backbending Principles

- Strong legs – Inner thighs engage and rotate inward

- Core support – Belly in and up protects lower back

- Shoulder blade action – Firm tips toward each other

- Even distribution – Spread extension across entire spine

Counterpose – Always follow with forward fold or child’s pose

FAQ: Yoga Anatomy Questions Answered

Individual anatomy varies significantly in bone structure, muscle fiber composition, joint capsule tightness, and nervous system sensitivity. Two people with identical flexibility can experience the same pose completely differently based on their unique skeletal proportions and soft tissue characteristics.

Productive stretching creates a pulling or lengthening sensation in the belly of the muscle that’s tolerable and gradually decreases as you hold the position. Warning signs include sharp pain, burning sensations, pain in joints rather than muscles, numbness or tingling, and pain that increases rather than decreases while holding.

Research shows static stretches need at least 20-30 seconds to begin affecting muscle length, with optimal results at 60-90 seconds. However, holding too long (over 2 minutes) may trigger protective reflexes. For yoga practice, holding poses for 5-8 breaths (30-60 seconds) balances effectiveness with safety.

Intense static stretching before strength work can temporarily reduce muscle power and stability. Begin with dynamic movement (like sun salutations), do your strength-focused poses, then include deeper static stretches toward the end of practice when muscles are warm and more receptive.

Daily fluctuations in flexibility are normal and influenced by hydration, sleep quality, stress levels, time of day, recent physical activity, temperature, and hormonal changes. Your body’s natural flexibility typically peaks in the afternoon (2-4 PM) and is lowest in early morning.

Conclusion: Your Body, Your Practice

This yoga anatomy guide provides the foundation for understanding how your remarkable body moves, stabilizes, and adapts through yoga practice. Remember that anatomical knowledge serves your practice—it doesn’t restrict it. Use this information to make informed choices, respect your body’s unique design, and practice with both courage and wisdom.

Every body is different, which means your yoga journey is uniquely yours. Some practitioners naturally excel at balance poses while others find inversions more accessible. Rather than forcing your body into predetermined shapes, use anatomical awareness to explore what’s possible for you while honoring what isn’t.

The more you understand about muscles, joints, and movement mechanics, the more empowered you become to practice safely, prevent injuries, and experience the profound benefits yoga offers at every stage of life. Ready to deepen your practice? Explore our related articles on Warrior Pose variations, safe Virasana modifications, effective yoga twists, challenging inversions, and essential balance poses to continue your anatomical education.